Kidneys 101: Vital Roles, Early Warning Signs & Care Advice

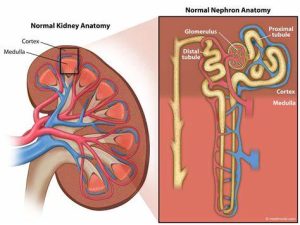

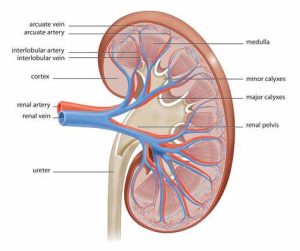

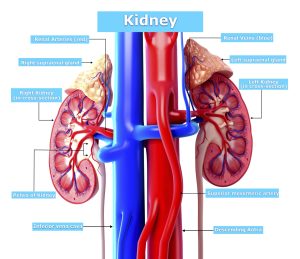

Every person has 2 kidneys, which are located above the waist on both sides of the spine. These reddish-brown, bean-shaped organs are each about the size of a small fist. They are located closer to the back of the body than to the front.

The kidneys filter blood to remove impurities, excess minerals and salts, and extra water. Every day, the kidneys filter about 200 quarts of blood to generate 2 quarts of urine. The kidneys also produce hormones that help control blood pressure, red blood cell production, and other bodily functions.

Most people have 2 kidneys. Each kidney works independently. This means the body can function with less than 1 complete kidney. With dialysis, a mechanized filtering process, it is possible to live without functioning kidneys. Dialysis can be done through the blood, called hemodialysis, or by using the patient’s abdominal cavity, called peritoneal dialysis.

About kidney cancer

Kidney cancer begins when healthy cells in 1 or both kidneys change and grow out of control, forming a mass called a renal cortical tumor. A tumor can be malignant, indolent, or benign. A malignant tumor is cancerous, meaning it can grow and spread to other parts of the body. An indolent tumor is also cancerous, but this type of tumor rarely spreads to other parts of the body. A benign tumor means the tumor can grow but will not spread.

Types of kidney cancer

There are several types of kidney cancer:

- Renal cell carcinoma. Renal cell carcinoma is the most common type of adult kidney cancer, making up about 85% of diagnoses. This type of cancer develops in the proximal renal tubules that make up the kidney’s filtration system. There are thousands of these tiny filtration units in each kidney. The treatment options for renal cell carcinoma are discussed later in this guide.

- Urothelial carcinoma. This is also called transitional cell carcinoma. It accounts for 5% to 10% of the kidney cancers diagnosed in adults. Urothelial carcinoma begins in the area of the kidney where urine collects before moving to the bladder, called the renal pelvis. This type of kidney cancer is treated like bladder cancer because both types of cancer begin in the same cells that line the renal pelvis and bladder.

- Sarcoma. Sarcoma of the kidney is rare. This type of cancer develops in the soft tissue of the kidney; the thin layer of connective tissue surrounding the kidney, called the capsule, or the surrounding fat. Sarcoma of the kidney is usually treated with surgery. However, sarcoma commonly comes back in the kidney area or spreads to other parts of the body. More surgery or chemotherapy may be recommended after the first surgery.

- Wilms tumor. Wilms’ tumor is most common in children and is treated differently from kidney cancer in adults. Wilms tumors make up about 1% of kidney cancers. This type of tumor is more likely to be successfully treated with radiation therapy and chemotherapy than the other types of kidney cancer when combined with surgery. This has resulted in a different approach to treatment.

- Lymphoma. Lymphoma can enlarge both kidneys and is associated with enlarged lymph nodes, called lymphadenopathy, in other parts of the body, including the neck, chest, and abdominal cavity. In rare cases, kidney lymphoma can appear as a lone tumor mass in the kidney and may include enlarged regional lymph nodes. If lymphoma is a possibility, your doctor may perform a biopsy (see Diagnosis) and recommend chemotherapy instead of surgery.

Types of kidney cancer cells

Knowing which type of cell makes up a kidney tumor helps doctors plan treatment. Pathologists have identified more than 40 different types of kidney cancer cells. A pathologist is a doctor who specializes in interpreting laboratory tests and evaluating cells, tissues, and organs to diagnose disease. Computed tomography (CT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (see Diagnosis) cannot always show the difference between benign, indolent, or malignant renal cortical tumors before surgery.

The most common types of kidney cancer cells are listed below. In general, the grade of a tumor refers to the degree of differentiation of the cells, not how fast they grow. Differentiation describes how much the cancer cells look like healthy cells. The higher the grade, the more likely the cells are to spread or metastasize over time.

- Clear cell. About 70% of kidney cancers are made up of clear cells. Clear cells range from slow-growing (grade 1) to fast-growing (grade 4). Immunotherapy and targeted therapy (see Types of Treatment) are particularly effective at treating clear-cell kidney cancer.

- Papillary. Papillary kidney cancer is found in 10% to 15% of all kidney cancers. It is divided into 2 different subtypes, called type 1 and type 2. Localized, papillary kidney cancer is often treated with surgery. If papillary kidney cancer spreads or metastasizes, it is often treated with blood vessel-blocking agents. Using immunotherapy to treat metastatic papillary cancers is still being researched. Many doctors recommend treatment through a clinical trial for metastatic papillary cancers.

- Sarcomatoid features. Each of the tumor subtypes of kidney cancer (clear cell, chromophobe, and papillary, among others) can show highly disorganized features under the microscope. These are often described by pathologists as “sarcomatoid.” This is not a distinct tumor subtype, but when these features are seen, doctors are aware that this is a very aggressive form of kidney cancer. There is promising scientific research for immunotherapy treatment options for people with a tumor with sarcomatoid features. Most recently, this included the approved combinations of ipilimumab (Yervoy) and nivolumab (Opdivo), axitinib (Inlyta) and pembrolizumab (Keytruda), axitinib and avelumab (Bavencio), cabozantinib (Cabometyx) and nivolumab, and lenvatinib (Lenvima) and pembrolizumab, as well as the experimental combination of atezolizumab (Tecentriq) and bevacizumab (Avastin).

- Medullary. This is a rare and highly aggressive cancer, but it is still considered a renal cortical tumor. It is more common in Black people and is highly associated with having sickle cell disease or sickle cell trait. Sickle cell trait means that a person has inherited 1 copy of the sickle cell gene from a parent. Combinations of chemotherapy are currently recommended treatment options, and clinical trials are ongoing to better define treatment decisions.

- Collecting duct: Collecting duct carcinoma is more likely to occur in people between the ages of 20 and 30. It begins in the collecting ducts of the kidney. Therefore, collecting duct carcinoma is closely related to transitional cell carcinoma (see “Urothelial carcinoma” above). This cancer is difficult to treat successfully long-term, even with combinations of systemic chemotherapy and surgery.

- Chromophobe. Chromophobe is another uncommon cancer that may form indolent tumors that are unlikely to spread, but are aggressive if they do spread. Clinical trials are ongoing to find the best ways to treat this type of cancer.

- Oncocytoma. This is a slow-growing type of kidney cancer that rarely, if ever, spreads. The treatment of choice is surgery for large, bulky tumors.

- Angiomyolipoma. Angiomyolipoma is a benign kidney tumor that has a unique appearance on a CT scan and when viewed under a microscope. Usually, it is less likely to grow and spread. It is usually treated with surgery or, if it is small, with active surveillance (see Types of Treatment). Significant bleeding is a rare event, but more likely when female patients are pregnant and before menopause. An aggressive form of angiomyolipoma, called epithelioid, can, in rare instances, invade the renal vein and inferior vena cava and spread to nearby lymph nodes or organs, such as the liver.

How many people are diagnosed with kidney cancer?

In 2023, an estimated 81,800 adults (52,360 men and 29,440 women) in the United States will be diagnosed with kidney cancer. Worldwide, an estimated 431,288 people were diagnosed with kidney cancer in 2020.

In the United States, kidney cancer is the sixth most common cancer in men. It is the ninth most common cancer in women. The average age at diagnosis for people with kidney cancer is 64, and most people are diagnosed between the ages of 65 and 74. Kidney cancer is not common in people younger than age 45. It is more common in black people and American Indians.

The number of new kidney cancers in the United States has been increasing for several decades, although that increase has slowed in recent years. Between 2010 and 2019, rates rose by 1% each year. Some of the increase has been due to an increase in the overall use of imaging tests. Imaging tests can find small kidney tumors unexpectedly when the tests are done for another reason unrelated to the cancer.

It is estimated that 14,890 deaths (9,920 men and 4,970 women) from this disease will occur in the United States in 2023. However, the death rate has been going down since the mid-1990s. Between 2013 and 2020, deaths from kidney cancer decreased by around 2% per year. In 2020, an estimated 179,368 people worldwide died from kidney cancer.

What is the survival rate for kidney cancer?

Different types of statistics can help doctors evaluate a person’s chance of recovery from kidney cancer. These are called survival statistics. A specific type of survival statistic is called the relative survival rate. It is often used to predict how having cancer may affect life expectancy. The relative survival rate looks at how likely people with kidney cancer are to survive for a certain amount of time after their initial diagnosis or start of treatment, compared to the expected survival of similar people without this cancer.

Example: Here is an example to help explain what a relative survival rate means. Please note that this is only an example and not specific to this type of cancer. Let’s assume that the 5-year relative survival rate for a specific type of cancer is 90%. “Percent” means how many out of 100. Imagine there are 1,000 people without cancer, and based on their age and other characteristics, you expect 900 of the 1,000 to be alive in 5 years. Imagine that there are another 1,000 people similar in age and other characteristics to the first 1,000, but they all have the same specific type of cancer that has a 5-year survival rate of 90%. This means it is expected that 810 of the people with the specific cancer (90% of 900) will be alive in 5 years.

It is important to remember that statistics on the survival rates of people with kidney cancer are only an estimate. They cannot tell a person if cancer will or will not shorten their life. Instead, these statistics describe trends in groups of people previously diagnosed with the same disease, including specific stages of the disease.

The 5-year relative survival rate for kidney cancer in the United States is 77%.

The survival rates for kidney cancer vary based on several factors. These include the stage of cancer, a person’s age and general health, and how well the treatment plan works. Other factors that can affect outcomes include the type and cell type of the cancer when it is first diagnosed.

Researchers continue to study how tumor size, whether the cancer involves the lymph nodes, and how far the cancer has spread affect survival rates. Many of these studies calculate survival rates after surgery is done. These studies suggest that kidney cancer that spreads to the lymph nodes or distant areas of the body will have lower survival rates. However, recent advances in treatment, especially with immunotherapy (see Types of Treatment), are allowing some people with metastatic kidney cancer to live much longer than before.

About two-thirds of people are diagnosed when the cancer is located only in the kidney. For this group, the 5-year relative survival rate is 93%. If kidney cancer has spread to surrounding tissues or organs and/or the regional lymph nodes, the 5-year relative survival rate is 72%. If the cancer has spread to a distant part of the body, the 5-year relative survival rate is 15%.

Experts measure the relative survival rate statistics for kidney cancer every 5 years. This means the estimate may not reflect the results of advancements in how kidney cancer is diagnosed or treated over the last 5 years. Talk with your doctor if you have any questions about this information. Learn more about understanding statistics.

Statistics adapted from the American Cancer Society’s (ACS) publication, Cancer Facts & Figures 2023, the ACS website, and the International Agency for Research on Cancer website. (All sources accessed February 2023.)

What are the risk factors for kidney cancer?

A risk factor is anything that increases a person’s chance of developing cancer. Although risk factors often influence the development of cancer, most do not directly cause cancer. Some people with several known risk factors never develop cancer, while others with no known risk factors do. Knowing your risk factors and talking about them with your doctor may help you make more informed lifestyle and health care choices.

The following factors may raise a person’s risk of developing kidney cancer:

- Smoking. Smoking tobacco doubles the risk of developing kidney cancer. It is believed to cause about 30% of kidney cancers in men and about 25% in women.

- Sex. Men are 2 to 3 times more likely to develop kidney cancer than women.

- Race. Black people have higher rates of kidney cancer.

- Age. Kidney cancer is typically found in adults and is usually diagnosed between the ages of 50 and 70.

- Nutrition and weight. Research has often shown a link between kidney cancer and obesity.

- High blood pressure. People with high blood pressure, also called hypertension, may be more likely to develop kidney cancer.

- Overuse of certain medications. Painkillers containing phenacetin have been banned in the United States since 1983 because of their link to transitional cell carcinoma.

- Exposure to cadmium. Some studies have shown a connection between exposure to the metallic element cadmium and kidney cancer. Working with batteries, paints, or welding materials may increase a person’s risk as well. This risk is even higher for smokers who have been exposed to cadmium.

- Chronic kidney disease. People who have decreased kidney function but do not yet need dialysis may be at higher risk of developing kidney cancer.

- Long-term dialysis. People who have been on dialysis for a long time may develop cancerous cysts in their kidneys. These growths are usually found early and can often be removed before the cancer spreads.

- Family history of kidney cancer. People who have a strong family history of kidney cancer may have an increased risk of developing the disease. This can include individuals with first-degree relatives, such as a parent, brother, sister, or child. Risk also increases if other extended family members have been diagnosed with kidney cancer, including grandparents, aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, grandchildren, and cousins. Specific factors in family members may increase the risk of a hereditary kidney cancer disorder, including diagnosis at an early age, rare types of kidney cancer, cancer in both kidneys (called bilaterality), more than 1 tumor in the same kidney (called multifocality), and other types of benign or cancerous tumors.

If you are concerned that kidney cancer may run in your family, it is important to get an accurate family history and to share the results with your doctor. By understanding your family history, you and your doctor can take steps to reduce your risk and be proactive about your health.

Genetic conditions and kidney cancer

Although kidney cancer can run in families, inherited kidney cancers linked to a single, inherited gene are uncommon, accounting for 5% or less of kidney cancers. Over a dozen unique genes that increase the risk of developing kidney cancer have been found, and many are linked to specific genetic syndromes. Most of these conditions are associated with a specific type of kidney cancer (see Introduction).

Finding a specific genetic syndrome in a family can help a person and their doctor develop an appropriate cancer screening plan and, in some cases, help determine the best treatment options. Only genetic testing can determine whether a person has a genetic mutation. Most experts strongly recommend that people considering genetic testing first talk with someone with expertise in cancer genetics, such as a genetic counselor, who can explain the risks and benefits of genetic testing.

Genetic conditions that increase a person’s risk of developing kidney cancer include:

- Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL)-Syndrom. People with VHL syndrome have an increased risk of developing several types of tumors. Up to 60% of people with this disorder develop clear-cell kidney cancer.

- Hereditary papillary renal cell carcinoma (HPRCC). HPRCC is a very rare genetic condition that increases the risk of type 1 papillary renal cell carcinoma. People who have HPRCC have a very high risk of developing more than 1 kidney tumor in both kidneys, but do not have an increased risk for other cancers or conditions.

- Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome. BHD syndrome is a rare genetic condition associated with multiple noncancerous skin tumors, lung cysts, and an increased risk of noncancerous and cancerous kidney tumors. Tumors are most often chromophobes, oncocytomas, or a mixture of both, which are called hybrid tumors.

- Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC). HLRCC is associated with an increased risk of about 16% of developing a form of kidney cancer that resembles type 2 papillary or collecting duct renal cell carcinoma. Skin nodules called leiomyomata are often found, mainly on the arms, legs, chest, and back. HLRCC can often cause uterine fibroids, known as leiomyomas. Rarely, adrenal tumors can form.

- Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) syndrome. TSC syndrome is a genetic condition associated with changes in the skin, brain, kidney, and heart. More than half of individuals with TSC develop angiomyolipomas of the kidney. About 2% of those individuals will develop kidney cancer (see the Introduction).

- Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) complex syndrome. SDH is a related group of hereditary cancer syndromes associated with tumors called pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) and kidney cancers may also be related to this syndrome.

- BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome (BAP1 TPS). An inherited mutation in the BRCA1-associated protein 1 (BAP1) gene is associated with melanoma of the skin and of the eye, mesothelioma, and clear cell renal cell carcinoma.

Other genetic conditions may be associated with an increased risk of kidney cancer. Research to find other genetic causes of kidney cancer is ongoing.

Are there ways to prevent kidney cancer?

Different factors cause different types of cancer. Researchers continue to look into what factors cause kidney cancer, including ways to prevent it. Although there is no proven way to completely prevent kidney cancer, you may be able to lower your risk by:

- Quitting smoking

- Lowering blood pressure

- Maintaining a healthy body weight

- Eating a diet high in fruits and vegetables and low in fat

How are people screened for kidney cancer?

Routine screening tests to detect early kidney cancer are not available. Doctors may recommend that people with a high risk of the disease have imaging tests (see Diagnosis) to look inside the body. For people with a family history of kidney cancer, computed tomography (CT) scans or renal ultrasounds are sometimes used to search for early-stage kidney cancer. However, CT scans have not been proven to be a useful screening tool for kidney cancer for most people.

The next section in this guide is Symptoms and Signs. It explains what changes or medical problems kidney cancer can cause. Use the menu to choose a different section to read in this guide.

Kidney Cancer – Symptoms and Signs

What are the symptoms and signs of kidney cancer?

Often, kidney cancer is found when a person has an imaging test, such as an ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or computed tomography (CT) scan (see Diagnosis), for another reason. In its earliest stages, kidney cancer causes no pain. Therefore, symptoms of the disease usually appear when the tumor grows large and begins to affect nearby organs.

People with kidney cancer may experience one or more of the following symptoms or signs:. Symptoms are changes that you can feel in your body. Signs are changes in something measured, like taking your blood pressure or doing a lab test. Together, symptoms and signs can help describe a medical problem. Sometimes, people with kidney cancer do not have any of the symptoms and signs described below. In other cases, the cause of a symptom or sign may be a medical condition that is not cancer.

- Blood in the urine

- Pain or pressure in the side or back

- A mass or lump in the side or back

- Swelling of the ankles and legs

- High blood pressure

- Anemia, which is a low red blood cell count

- Fatigue

- Loss of appetite

- Unexplained weight loss

- Fever that keeps coming back and is not from a cold, flu, or other infection

- In the testicles, a rapid development of a cluster of enlarged veins, known as a varicocele, around a testicle, particularly the right testicle, may indicate that a large kidney tumor may be present

If you are concerned about any changes you experience, please talk with your doctor. Your doctor will try to understand what is causing your symptom(s). They may do an exam and order tests to understand the cause of the problem, which is called a diagnosis.

If cancer is diagnosed, relieving symptoms remains an important part of cancer care and treatment. Managing symptoms may also be called “palliative and supportive care,” which is not the same as hospice care given at the end of life. You can receive palliative and supportive care at any time during cancer treatment. This type of care focuses on managing symptoms and supporting people who face serious illnesses, such as cancer. You can receive palliative and supportive care at any time during cancer treatment. Learn more in this guide’s section on Coping with Treatment.

Be sure to talk with your health care team about the symptoms you experience, including any new symptoms or a change in symptoms.

Kidney Cancer – Stages

READ MORE BELOW

What is cancer staging?

Staging is a way of describing where the cancer is located, if or where it has spread, and whether it is affecting other parts of the body.

Doctors use diagnostic tests to find out the cancer’s stage, so staging may not be complete until all the tests are finished. Knowing the stage helps the doctor recommend the best kind of treatment, and it can help predict a patient’s prognosis, which is the chance of recovery. There are different stage descriptions for different types of cancer.

TNM staging system

One tool that doctors use to describe the stage is the TNM system. Doctors use the results from diagnostic tests and scans to answer these questions:

- Tumor (T): How large is the primary tumor? Where is it located?

- Node (N): Has the tumor spread to the lymph nodes? If so, where and how many?

- Metastasis (M): Has the cancer spread to other parts of the body? If so, where and how much?

The results are combined to determine the stage of cancer for each person.

There are 5 stages for kidney cancer: stage 0 (zero) and stages I through IV (1 through 4). Stage 0 kidney cancer is extremely rare. The stage provides a common way of describing the cancer so doctors can work together to plan the best treatments.

Here are more details on each part of the TNM system for kidney cancer.

Tumor (T)

Using the TNM system, the “T” plus a letter or number (0 to 4) is used to describe the size and location of the tumor. Tumors are measured in centimeters (cm). One inch equals about 2.5 cm.

The stage may also be divided into smaller groups that help describe the tumor in even more detail. This helps the doctor develop the best treatment plan for each patient. If there is more than 1 tumor, the lowercase letter “m” (which stands for “multiple”) is added to the “T” stage category. Specific tumor-stage information for kidney cancer is listed below.

TX: The primary tumor cannot be evaluated.

T0 (T zero): No evidence of a primary tumor.

T1: The tumor is found only in the kidney and is 7 cm or smaller at its largest area. There has been much discussion among doctors about whether this classification should only include a tumor that is 5 cm or smaller.

- T1a: The tumor is found only in the kidney and is 4 cm or smaller at its largest area.

- T1b: The tumor is found only in the kidney and is between 4 cm and 7 cm at its largest area.

T2: The tumor is found only in the kidney and is larger than 7 cm in its largest area.

- T2a: The tumor is only in the kidney and is more than 7 cm but not more than 10 cm at its largest area.

- T2b: The tumor is only in the kidney and is more than 10 cm in its largest area.

T3: The tumor has grown into major veins within the kidney or perinephric tissue, which is the connective, fatty tissue around the kidneys. However, it has not grown into the adrenal gland on the same side of the body as the tumor. The adrenal glands are located on top of each kidney and produce hormones and adrenaline to help control heart rate, blood pressure, and other bodily functions. In addition, the tumor has not spread beyond Gerota’s fascia, an envelope of tissue that surrounds the kidney.

- T3a: The tumor has spread to the large vein leading out of the kidney, called the renal vein, or the branches of the renal vein; the fat surrounding and/or inside the kidney; or the pelvis and calyces of the kidney, which collect urine before sending it to the bladder. The tumor has not grown beyond Gerota’s fascia.

- T3b: The tumor has grown into the large vein that drains into the heart, called the inferior vena cava, below the diaphragm. The diaphragm is the muscle under the lungs that helps with breathing.

- T3c: The tumor has spread to the vena cava above the diaphragm and into the right atrium of the heart or to the walls of the vena cava.

T4: The tumor has spread to areas beyond Gerota’s fascia and extends into an adjacent organ, including the adrenal gland, liver, intestines, spleen, or pancreas.

Node (N)

The “N” in the TNM staging system stands for lymph nodes. These small, bean-shaped organs help fight infection. Lymph nodes near the kidneys are called regional lymph nodes. Lymph nodes in other parts of the body are called distant lymph nodes.

NX: The regional lymph nodes cannot be evaluated.

N0 (N zero): The cancer has not spread to the regional lymph nodes.

N1: The cancer has spread to regional lymph nodes.

Metastasis (M)

The “M” in the TNM system describes whether the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, called metastasis. Common areas where kidney cancer may spread include the bones, liver, lungs, brain, and distant lymph nodes.

M0 (M zero): The disease has not metastasized.

M1: The cancer has spread to other parts of the body beyond the kidney area.

Stage groups for kidney cancer

Doctors assign the stage of the cancer by combining the T, N, and M classifications (see above).

Stage I: The tumor is 7 cm or smaller and is only located in the kidney. It has not spread to the lymph nodes or distant organs (T1, N0, M0).

Stage II: The tumor is larger than 7 cm and is only located in the kidney. It has not spread to the lymph nodes or distant organs (T2, N0, M0).

Stage III: Either of these conditions:

- A tumor of any size is located only in the kidney. It has spread to the regional lymph nodes but not to other parts of the body (T1 or T2, N1, M0).

- The tumor has grown into major veins or perinephric tissue and may or may not have spread to regional lymph nodes. It has not spread to other parts of the body (T3, any N, or M0).

Stage IV: Either of these conditions:

- The tumor has spread to areas beyond Gerota’s fascia and extends into the adrenal gland on the same side of the body as the tumor, possibly to lymph nodes, but not to other parts of the body (T4, any N, M0).

- The tumor has spread to any other organ, such as the lungs, bones, or brain (any T, any N, or M1).

Recurrent: Recurrent cancer is cancer that has come back after treatment. It may be found in the kidney area or in another part of the body. If the cancer does return, there will be another round of tests to learn about the extent of the recurrence. These tests and scans are often similar to those done at the time of the original diagnosis.

Used with permission of the American College of Surgeons, Chicago, Illinois. The original and primary source for this information is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, Eighth Edition (2017), published by Springer International Publishing.

Prognostic factors

Doctors need to learn as much as possible about the tumor. This information can help them predict if the cancer will grow and spread or how effective treatment will be. This information includes:

- Cell type, such as clear cell, papillary, chromophobe, or another type (see Introduction)

- Grade, which describes how similar the cancer cells are to healthy cells

- Personal information, such as the person’s activity level and body weight

- Presence or absence of fevers, sweats, and other symptoms

- Laboratory test findings, such as red blood cell counts, white blood cell counts, and calcium levels in the blood

Information about the cancer’s stage will help the doctor recommend a specific treatment plan. The next section in this guide is Types of Treatment. Use the menu to choose a different section to read in this guide.

Kidney Cancer – Types of Treatment

ON THIS PAGE: You will learn about the different types of treatments doctors use to treat people with kidney cancer. Use the menu to see other pages.

This section explains the types of treatments, also known as therapies, that are the standard of care for kidney cancer. “Standard of care” means the best treatments known. Information in this section is based on medical standards of care for kidney cancer in the United States. Treatment options can vary from one place to another.

When making treatment plan decisions, you are encouraged to discuss with your doctor whether clinical trials offer additional options to consider. A clinical trial is a research study that tests a new approach to treatment. Doctors learn through clinical trials whether a new treatment is safe, effective, and possibly better than the standard treatment. Clinical trials can test a new drug, a new combination of standard treatments, or new doses of standard drugs or other treatments. Clinical trials are an option for all stages of cancer. Your doctor can help you consider all your treatment options. Learn more about clinical trials in the About Clinical Trials and Latest Research sections of this guide.

How kidney cancer is treated

In cancer care, different types of doctors who specialize in cancer, called oncologists, often work together to create a patient’s overall treatment plan that combines different types of treatments. This is called a multidisciplinary team. For kidney cancer, the health care team usually includes these specialists:

- Urologist. A doctor who specializes in the genitourinary tract, which includes the kidneys, bladder, genitals, prostate, and testicles.

- Urologic oncologist. A urologist who specializes in treating cancers of the urinary tract.

- Medical oncologist. A doctor trained to treat cancer with systemic treatments using medications.

- Radiation oncologist. A doctor trained to treat cancer with radiation therapy. This doctor will be part of the team if radiation therapy is recommended.

Cancer care teams include other health care professionals, such as physician assistants, nurse practitioners, oncology nurses, social workers, pharmacists, counselors, dietitians, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and others. Learn more about the clinicians who provide cancer care.

Treatment options and recommendations depend on several factors, including the cell type and stage of cancer, possible side effects, and the patient’s preferences and overall health. Take time to learn about all of your treatment options and be sure to ask questions about things that are unclear. Talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment and what you can expect while receiving treatment. These types of conversations are called “shared decision-making.” Shared decision-making is when you and your doctors work together to choose treatments that fit the goals of your care. Shared decision-making is important for kidney cancer because there are different treatment options. Learn more about making treatment decisions.

Kidney cancer is most often treated with surgery, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, or a combination of these treatments. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy are occasionally used. People with kidney cancer that has spread, called metastatic cancer (see below), often receive multiple lines of therapy. This means treatments are given one after another.

The common types of treatments used for kidney cancer, as well as different disease states of kidney cancer, are described below. Your care plan also includes treatment for symptoms and side effects, an important part of cancer care.

READ MORE BELOW

- Active surveillance

- Surgery

- Non-surgical tumor treatments

- Targeted therapy

- Immunotherapy

- Chemotherapy

- Radiation therapy

- Physical, social, emotional, and financial effects of cancer

- Metastatic kidney cancer

- Remission and the chance of recurrence

- If treatment does not work

Active surveillance

Sometimes, the doctor may recommend closely monitoring the tumor with regular diagnostic tests and clinic appointments. This is called “active surveillance.” Active surveillance may be recommended in older adults and people who have a small renal tumor and other serious medical conditions, such as heart disease, chronic kidney disease, or severe lung disease. Younger people who have small kidney masses (smaller than 5 cm) may also be recommended to undergo active surveillance due to the low likelihood of the tumor spreading. Active surveillance may also be used for some people with kidney cancer, as long as they are otherwise well and have few or no symptoms, even if the cancer has spread to other parts of the body. Systemic therapies (see “Therapies using medication” below) can be started if it looks like the disease is getting worse.

Active surveillance is not the same as “watchful waiting” for kidney cancer. While active surveillance uses interval diagnostic scans, watchful waiting involves regular appointments to review symptoms, but patients do not have regular diagnostic tests, such as biopsies or imaging scans. The doctor simply watches for symptoms. If symptoms suggest that action is needed, then a new treatment plan is considered.

Surgery

Surgery is the removal of the tumor and some surrounding healthy tissue during an operation. If the cancer has not spread beyond the kidneys, surgery to remove the tumor may be the only treatment needed. Surgery to remove the tumor may mean removing part or all of the kidney, as well as possibly nearby tissue and lymph nodes.

Types of surgery used for kidney cancer include the following procedures:

- Radical nephrectomy. Surgery to remove the tumor, the entire kidney, and surrounding tissue is called a radical nephrectomy. If nearby tissue and surrounding lymph nodes are also affected by the disease, a radical nephrectomy and lymph node dissection are performed. During a lymph node dissection, the lymph nodes affected by the cancer are removed. If the cancer has spread to the adrenal gland or nearby blood vessels, the surgeon may remove the adrenal gland during a procedure called an adrenalectomy, as well as parts of the blood vessels. A radical nephrectomy is usually recommended to treat a large tumor when there is not much healthy tissue remaining. Sometimes the renal tumor will grow directly inside the renal vein and enter the vena cava on its way to the heart. If this happens, complex cardiovascular surgical techniques are needed.

- Partial nephrectomy. A partial nephrectomy is the surgical removal of the tumor. This type of surgery preserves kidney function and lowers the risk of developing chronic kidney disease after surgery. Research has shown that partial nephrectomy is effective for T1 tumors whenever surgery is possible. Newer approaches that use a smaller surgical incision, or cut, are associated with fewer side effects and a faster recovery.

- Laparoscopic and robotic surgery (minimally invasive surgery). During laparoscopic surgery, the surgeon makes several small cuts in the abdomen, rather than one larger cut used during a traditional surgical procedure. The surgeon then inserts telescoping equipment into these small keyhole incisions to completely remove the kidney or perform a partial nephrectomy. Sometimes, the surgeon may use robotic instruments to operate. This surgery may take longer, but it may be less painful. Laparoscopic and robotic approaches require specialized training. It is important to discuss the potential benefits and risks of these types of surgery with your surgical team and to be certain that the team has experience with the procedure.

- Cytoreductive nephrectomy. A cytoreductive nephrectomy is the surgical removal of the primary kidney tumor along with the whole kidney in cases where the disease has spread beyond the kidney. This may be recommended after diagnosis or after other systemic treatments have already been started. There is growing evidence that, in metastatic disease, starting systemic treatments first is helpful. There are ongoing clinical trials evaluating the best time for cytoreductive nephrectomy after treatment with immunotherapy (see below).

- Metastasectomy. Metastasectomy is the surgical removal of a single site of disease, such as the lung, pancreas, liver, or other site, to cure the cancer. This surgery is generally recommended for people who will benefit from the removal of a single site of kidney cancer spread.

Before any type of surgery, talk with your health care team about the possible side effects from the specific surgery you will have. Learn more about the basics of cancer surgery.

Non-surgical tumor treatments

Sometimes surgery is not recommended because of the characteristics of the tumor or the patient’s overall health. Every patient should have a thorough conversation with their doctor about their diagnosis and risk factors to see if these treatments are appropriate and safe for them. The following procedures may be options:

- Radiofrequency ablation. During radiofrequency ablation (RFA), a needle is inserted into the tumor to destroy the cancer with an electric current. The procedure is performed by an interventional radiologist or urologist. The patient is sedated and given local anesthesia to numb the area. In the past, RFA has only been used for people who were too sick to have surgery. Today, most patients who are too sick for surgery are monitored with active surveillance instead (see above), and patients who have locally advanced disease may also be recommended to have systemic treatments (see below).

- Cryoablation. During cryoablation, also called cryotherapy or cryosurgery, a metal probe is inserted through a small incision into cancerous tissue to freeze the cancer cells. A computed tomography (CT) scan and an ultrasound are used to guide the probe. Cryoablation requires general anesthesia for several hours and is performed by an interventional radiologist. Some surgeons combine this technique with laparoscopy to treat the tumor, but there is not much long-term research evidence to prove that it is effective.

Therapies using medication

The treatment plan may include medications to destroy cancer cells. Medication may be given through the bloodstream to reach cancer cells throughout the body. When a drug is given this way, it is called systemic therapy. Medication may also be given locally, which is when the medication is applied directly to the cancer or kept in a single part of the body.

This treatment is generally prescribed by a medical oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating cancer with medication.

Systemic medications are often given through an intravenous (IV) tube placed into a vein using a needle or as a pill or capsule that is swallowed orally. If you are given oral medications to take at home, be sure to ask your health care team about how to safely store and handle them.

The types of medications used for kidney cancer include:

- Targeted therapy

- Immunotherapy

- Chemotherapy

Each of these types of therapies is discussed below in more detail. A person may receive 1 type of medication at a time or a combination of medications given at the same time. They can also be given as part of a treatment plan that includes surgery and/or radiation therapy.

The medications used to treat cancer are continually being evaluated. Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications prescribed for you, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions with other medications.

It is also important to let your doctor know if you are taking any other prescription or over-the-counter medications or supplements. Herbs, supplements, and other drugs can interact with cancer medications, causing unwanted side effects or reduced effectiveness. Learn more about your prescriptions by using searchable drug databases.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a treatment that targets the cancer’s specific genes, proteins, or the tissue environment that contributes to cancer growth and survival. This type of treatment blocks the growth and spread of cancer cells and limits damage to healthy cells.

Not all tumors have the same targets. Research studies continue to find out more about specific molecular targets and new treatments directed at them. Learn more about the basics of targeted treatments.

- Understanding Liver Cancer Definition, Causes, Types, Symptoms, Risk Factors & More

- Appendix Cancer Explained: Tumor Types and Key Symptoms